The restriction of the fundamental right to freedom of assembly, the intensified anti-EU rhetoric, the show of political power through the units of the Hungarian Counter-Terrorism Centre (TEK) showing up in Bosnia, supporting far-right political forces in Europe – one could enumerate at length the older and more recent cases that have made Viktor Orbán known as a politician seen by many as trying to create the Hungarian version of the Russian political model, and who sometimes makes decisions for which there is no clear justification based on Hungarian interests. If one were to put it mildly, although his country is in the EU, Orbán is pursuing a kind of domestic and foreign policy of his own which the Russian leadership does not seem to mind at all.

Orbán's critics are keen to put forward theories that it was under some kind of coercion that the head of the Hungarian government has been shaping Hungary's foreign policy this way. Those who buy into these theories prefer to formulate their suspicions without any evidence. These conspiracy theories should be treated with deep reservations, not only because of the lack of evidence, but also because while some have suspected the mafia, blackmail and all sorts of other things in the background, there is a simpler, rational explanation for why the Prime Minister changed course after 2010 without being forced to do so by any external force. And there is an explanation for his attraction to a Hungarianised, lighter version of the Russian model and the advancement of a Christian nationalist ideology in the name of which his government has now started to curtail basic freedoms.

In 2008, when Russia invaded Georgia (as it later did with Ukraine), Orbán criticised Western politicians for standing by and tolerating Russian aggression. At the same time, he found that even though Western leaders criticised Moscow for attacking Georgia, they continued to do business with the Russians. It is for this reason that some attribute his turnaround a year later to the fact that he felt that there was no point in him confronting the Russians if there is nothing he can gain from it, either at home or abroad. Moreover, none of the governments preceding his second term had done much to make the country independent from Russia in terms of energy, leaving Orbán with little room for manoeuvre on this issue. He had to adapt.

Not only has Orbán experienced the hypocrisy of the Western power elites, this statement has become a recurring element in his government's communications. In the summer of 2024, for example, Foreign Minister Péter Szijjártó spoke at the government-affiliated MCC Fest and said that the Americans and the French have continued to do business with the Russians, while European countries, including Poland, were buying Russian oil via India and other countries. At the time, the Foreign Minister said that "all of Europe is doing business with the Russians", but that the liberal, mainstream media had failed to draw attention to this. Zsolt Hernádi, the CEO of MOL, the Hungarian oil-giant has frequently expressed a similar view, saying that even the most critical Western European countries have continued to buy or ship Russian energy sources, they just don't publicize it. Another recurring element from the ruling party is that Hungary does not want to engage in a confrontation with Moscow because it is extremely dependent on Russian gas.

The realisation

Orbán and Putin first met in 2009. It was a time when everyone was still reeling from the effects of the 2008 global economic crisis, when the global system seemed to have suffered a 'leak', with the West likely to be on the losing end.

It was at this point that Orbán came to the realisation that the West had lost ground and that a certain sort of geopolitical realignment was taking place in favor of the Eastern powers.

During this period, this same vision was also being affirmed to Orbán by György Matolcsy, whose words at the time he still heeded. Although Matolcsy has since then fallen out of favour with him, his intellectual legacy remains. Indeed, the Prime Minister may well have concluded from what has happened since then that what he believed to be coming in 2008 has materialised. And finally, after Trump's second victory, the United States is abdicating its geopolitical status of its own accord, leaving not only Ukraine but also the European Union to fend for itself.

When Putin first met Orbán – who was still in opposition at the time –, the situation was somewhat similar to the sharp turn we are now witnessing in Russian-American relations. After the meeting in St Petersburg, Orbán, who until then could not be described as pro-Russian, got up from the table feeling that it was possible to do good business with the Russians after all, and that this was not just the prerogative of socialist, left-wing Hungarian governments.

In addition to the business aspect, Orbán also understood that with the expected two-thirds majority behind him, he would practically be able to shape Hungary's destiny any way he pleased. And for a leader embarking on such a grandiose transformation, the Russian illiberal model is much more comfortable than the classic form of liberal democracy. He regards the former as more decisive and ballsy, and the latter as ineffectual, gutless and overly bureaucratic.

Moreover, in the Russian model, the rich oligarchs are dependent on the country's number one leader. This became a really important aspect when, after having a dispute with his former comrade-in-arms and party financier Lajos Simicska, Orbán realised how important it was not to have an internal economic force on which he would have to depend affecting his informal power. In this model, the main authority is his alone, all the rest is just a prop, all the others are just political extras. This does not mean, of course, that all of this only exists to serve Orbán's interests alone, as the regime he has built has many beneficiaries besides him – not only in some sections of the electorate but also amongst the new elite that has emerged in the meantime.

Implementing a Hungarianised version of the Russian model is worth every penny for the head of the Hungarian government. He has even given up EU funds which were withheld by the EU, that would be needed to sustain the business circles surrounding his government (known as NER – see below). And it is no small amount either, we are talking about nearly EUR 10 billion, which Orbán is apparently willing to let go of.

NER is short for Nemzeti Együttműködés Rendszere, meaning ’System of National Cooperation.’ The term was coined by the Orbán government after their election victory in 2010 to refer to the changes in government that they were about to introduce. By now, NER has become a word in its own right, and is used in colloquial Hungarian to refer to Fidesz' governing elite, complete with the politicians and the oligarchs profiting from the system.

A pebble in the shoe

Not only has Brussels become a figurative opponent for Orbán, but a real political one as well. Although manufacturing an enemy is essentially symbolic and serves communication purposes, it cannot be explained solely on that basis. And while the hands of Russia's leader are not tied by an external force, Hungary is still a member of the EU – although Brussels is clearly not up to the task of dealing with the Hungarian issue. Withholding money will not steer Orbán away from the path he has set out on. Even so, it follows that Orbán would prefer an EU whose internal functioning and decision-making is not characterised by federalism. He would prefer Brussels to function as a kind of service provider, with individual member states doing whatever they want, whether it is the specific way in which they spend EU money, approach the rule of law or the way they conduct foreign relations.

This is what János Lázár (Minister of Construction and Transportation) referred to just a few days ago when he said that we need to regain the rights we lost when we joined the EU, and that is why we are fighting against the "global powers" as he said, to "protect our sovereignty". Fidesz is well aware that not only would the majority of the Hungarian population oppose Hungary leaving the EU, but so would the majority of Fidesz voters, which is why Orbán is not talking about leaving the EU, but about ‘taking it’, transforming it and moulding it into their own image. This has been their goal for a long time, and in alliance with the European far right, it is more realistic than when Fidesz left the EPP and found itself in the middle of nowhere.

The Patriots for Europe EP Group, the new far-right home of Fidesz, is also calling for a change in the EU. According to their manifesto, the EU wants to replace the nations as a centralised state with institutions largely unknown to and distant from European citizens. The patriots intend to prevent this, and one of their means for doing so is the caricature-like image of the enemy, in which a globalist government from 'Brussels' is directing everything in cahoots with liberal think tanks. Orbán believes that with Trump's victory, the globalists have lost ground in Washington, so they have fled to Brussels and must now be driven out from there. Brussels is to Orbán what the deep state is to Trump. Their opponents are different, but the paranoia is shared. The intellectual ammunition for this ideological battle is provided indirectly, but not to a negligible extent, by Russia. For the far-right political forces that see Brussels as the empire, the enemy, the authoritarian model offered by Moscow provides an ideology and an image of the enemy that they can exploit politically:

a political software that can also function in a democratic hardware.

Anti-globalisation, anti-migration, incitement against sexual minorities are all familiar elements of Russian propaganda. European politicians who are fighting for 'normality' can also rely on these, even if they do not back the Russians or collaborate with Putin.

The Russians have thus not only offered energy, oil and gas to some Western politicians, but also an identity politics which the latter can organically integrate into their own politics, making it their backbone. In this way they can present themselves as the defenders of Christian Europe in their respective communities.

Of course, this is all an illusion, since no one can seriously believe that a politician who dehumanises his political opponents and sides with mass murderers in international relations is a Christian in the classical sense of the word. Just as a politician who only cares about freedom of speech and expression only as long as he hears what he likes is obviously not a liberal.

The actions of political forces that claim to be liberal and those that claim to be Christian, but are otherwise interested in the polarisation of society, are also impacting each other. The reason why Christian nationalism has been able to take off is that extremism, such as cancel culture, has also appeared in the liberal discourse in the West, and has often really gone up against common sense, i.e. liberalism in the classical sense. Although to varying degrees, the two sides have collectively dug such deep ideological trenches that identity politics has become so powerful that it has eclipsed common sense.

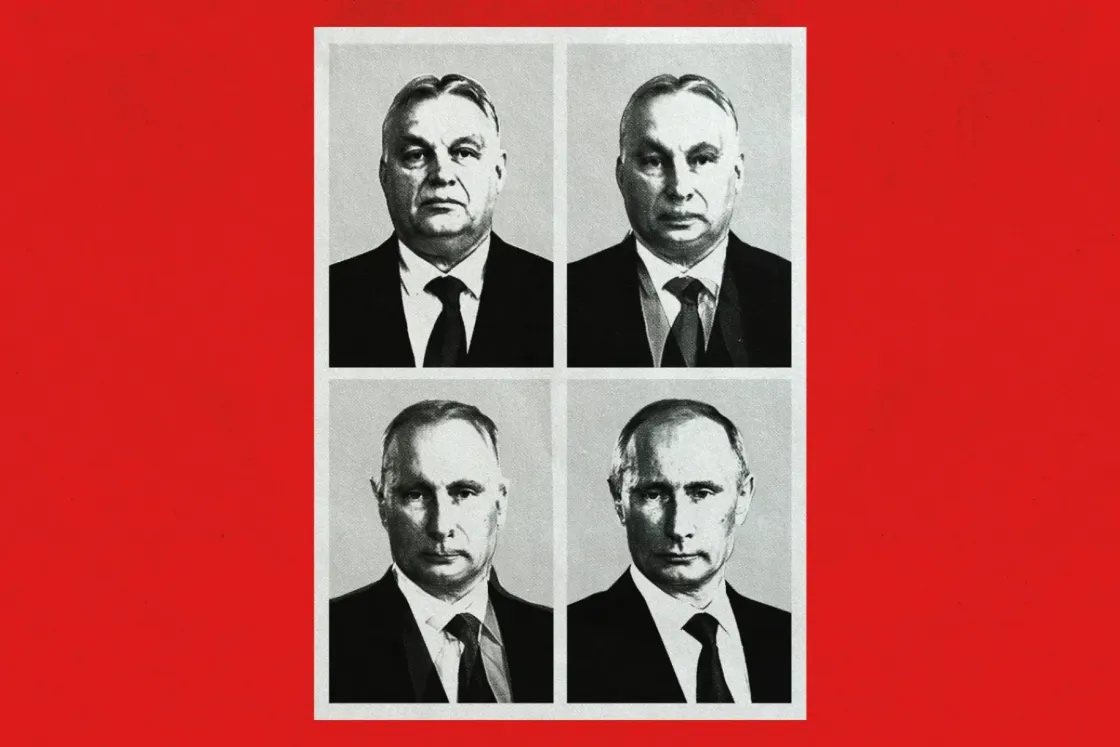

In this sense, Orbán is not Putin's puppet, as some of his critics would have us believe, but rather a kind of ideological, political ally.

Or, in other words, Orbán and Putin shop in the same political shop. These ideological similarities are the reason why the narrative of the Hungarian government and Fidesz overlaps with Russian propaganda. There is no need for them to overlap completely, it is enough if they are on the same page about the key topics (migration, homosexuality, globalization). This is the Kremlin's way of gaining influence in the Western world, while the Western political forces promoting Christian nationalist ideology, including the Trumpist MAGA movement in the United States, are interested in securing a stable identity for their current and future voters.

And this is how they aim to distinguish themselves from their political opponents, although it is more than a simple domestic political game. And it did not start yesterday either. This ideological rapprochement between the Hungarian ruling party and Moscow has been going on for many years, and the overlap between Russian propaganda and the content of the government controlled press was already evident in 2018. The seizure of public media, the regularizing of the press, the crackdown on independent media, the ousting of CEU (Central European University), the emergence of entities that look like NGOs, but which in fact represent government propaganda, the informal exercise of power over state institutions, the emergence of fake political parties, are all part of a phenomenon that is already well known in Russia.

The central element is undoubtedly communication and the influencing of the voters' perception of the world. After the invasion of Crimea in 2014, Russia launched a disinformation campaign focusing on migration, LGBTQ rights, traditional (conservative) values, and the growing depopulation and impoverishment of the EU. After February 2022, not only did it add anti-Ukraine rhetoric to this but it also started targeting the EU even more, claiming that Brussels was weak and it was a poor representative of Ukraine's interests anyway. These phrases may be familiar from the Hungarian government-friendly press, as well as from the speeches of Fidesz organisations masquerading as NGOs.

The catalyst

Even if Orbán expected the 2008 global economic crisis to lead to a geo-political realignment, he did not want to go against this process, but became a catalyst using his own, at that time modest means – precisely because he knew that he could benefit from it in terms of leverage. As the leader of an EU country, he was the first to enter a political niche market where he had no serious competitors. But he also had the courage to defy taboos and build his own brand in the international arena. While capitalising on the economic boom and the EU funds flowing into the country, he built a stable economic base with a well-functioning power apparatus, allocating most of his resources to communication, and strengthening the identity politics from which he hopes to derive legitimacy.

In 2014, Fidesz attacked Jobbik claiming that one of its MEPs, Béla Kovács, had spied for the Russians against the EU institutions. Years later, Kovács was convicted in a court of law, but the Hungarian state still allowed him to run, and the former politician has since then been living in Russia, where he has been granted political asylum. And what did Kovács, the spy do? For example, he tried to unite the – at that time still unsavoury – European far-right in order to shape EU policy to the benefit of the Russians. Even though Orbán is not pandering to the Russians, but is working for his own benefit, he is doing the same thing: allying with far-right forces, just as Béla Kovács did before.

Béla Kovács was also the MEP who, after the occupation of Crimea, legitimised the Russian-friendly referendum in Crimea. This may also sound familiar. Last year, the European Parliament adopted a resolution condemning the parliamentary elections in the EU candidate country of Georgia on 26 October for being neither free nor fair and for contributing to the deterioration of Georgian democracy. The pro-Russian Georgian Dream rose to power in Georgia, and Viktor Orbán was the only EU leader to rush to congratulate the winner. Such moves can no longer be explained by domestic political goals, but they are not in the Hungarian interest either.

This does not mean that Béla Kovács and Viktor Orbán can be mentioned in the same breath, because one of them is a proven Russian spy, while the other is at best only taunted as being one. What these actions do show, however, is that not only do similarities exist in the Russian and Hungarian political models, but also between the actions of a Russian spy and the head of the Hungarian government. All of this, in turn, indicates the existence of a greater strategy, which is about much more than a communication power game in the domestic arena or an attempt to create hysteria and rile up opposition voters. Moreover, this process is already taking place in the international arena, on the big stage, far beyond Hungary.

While he strongly condemned Russia’s intervention in Georgia in 2008, during the seizure of Crimea in 2014 Orbán no longer advocated a policy of resistance but of acceptance, as if resigned to the fact that if Moscow wants to regain the influence it lost when communism collapsed, then it should be allowed to do so.

The permissive one

"The Russians' goal to go back to how things used to be does not appear to be unrealistic. It is in this context that we need to think about the relationship between the European Union and Russia," the Hungarian Prime Minister said in a speech in Tusványos in 2018.

The above sentence was interpreted by many as Orbán predicting the Russian-Ukrainian war which started in 2022. It was in this same speech that he said that Ukraine, which had up until then been part West and part East, had decided that it wanted to belong to the West, but according to Orbán, neither NATO nor EU membership was realistic for them.

It was also at that time that Orbán spoke of the EU's primitive policy towards Russia, which he called "a policy of sanctions and security threats". While he admitted that there are EU countries that might indeed feel threatened (among them the Baltic states and Poland), he said that Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Western Europe do not feel such a threat. Orbán then suggested that the EU and NATO should give extra security guarantees to the European states under threat, but should allow the rest of Europe to keep trading with Russia.

Even his 2018 speech at Tusványos indicated that Orbán does not want to sacrifice his government’s policy of Eastern opening – which also serves as ideological support – on the altar of the Western alliance system, irrespective of what Russia might do with Ukraine.

The Hungarian Prime Minister wants Hungary to be part of the Western alliance system while maintaining good relations with Russia.

The Ukrainians may be familiar with this balancing act: under their former pro-Russian president, Viktor Yanukovych, Ukraine was seen as a Russian ally, but was also courting the West, which Moscow did not approve of. However, this seesaw policy ended badly, with mass protests breaking out in Kyiv after Yanukovych pulled out of the Association Agreement with the EU, forcing the Ukrainian President to flee to Russia. Orbán is doing something similar, but in the other direction: he is de facto part of the Western alliance system, but he is doing business and making ideological alliances with Eastern despots. Thus, what was after 2010 for years merely a matter of the rule of law is now much more than that: it is a battle between East and West.

This ideological alliance has become so strong that it has even overruled the 'Orbán from 2008'. According to the current interpretation of the Hungarian Prime Minister, the West provoked Moscow by trying to lure Ukraine to itself. If we accept this explanation, it also follows that Ukraine did not have the right to self-determination and sovereignty in the first place – at least according to Orbán. This is what shuttlecock politicking is: when a politician sometimes says one thing and then switches to another. Although it is certainly no longer the case today, in December 2022, at an international press conference, Viktor Orbán said that the existence of a sovereign Ukraine was in Hungary's interest.

Gestures with no Hungarian interest

In light of the above, it is not surprising that after Russia attacked Ukraine in 2022, and the Western states that had been doing business with Russia confronted Moscow, Orbán did not adjust his policy towards Russia, although many expected him to be forced to do so. Instead, just as he did after the invasion of Crimea in 2014, he has been opposing sanctions against Russia from 2022 onwards, blaming them and the "misguided sanctions policy of Brussels" for Hungary's deteriorating economic performance.

Orbán has regularly threatened to veto the sanctions, which need to be renewed every six months, but has ended up voting for them at the last minute each time. It is on the heels of this eccentric policy that he keeps making gestures to Moscow: from challenging sanctions against the genuinely pro-war Patriarch Kirill on the grounds of religious freedom, to lobbying for Russian oligarchs, to opposing Sweden's accession to NATO, to celebrating the victory of the Russian puppet government that won in Georgia under questionable circumstances. But we could also mention Bosnia, where Orbán has openly sided with the pro-Russian Milorad Dodik, risking the destabilisation of an already volatile country.

These are steps where it is difficult to find the Hungarian interest even if one looks for them with a magnifying glass. And the question is, to what extent Orbán's policies are in sync with those of his advisers. A good example of this is the fact that, under Marcell Bíró's command, Imre Porkoláb was appointed as one of the Prime Minister's national security advisors last spring. In an interview with Mandiner in the autumn of 2023 Porkoláb said: Sweden's accession would make NATO stronger, so it is in the interest of both the alliance and Hungary that Sweden joins. Porkoláb made this point at the time when Orbán was actively obstructing the Swedes' accession to NATO.

The latter has given many the impression that Orbán is playing into the hands of the Russians. While there was absolutely nothing that Hungary gained by harassing the Swedes, the constant wrangling only reinforced the impression that the Western military defence alliance was not united on the subject. The so-called ''policy of peace'', which is also an integral part of Russian propaganda – and, according to some, much more than that – fits into the same mold. This ''policy of peace'' does not blame the war between Russia and Ukraine on the aggressor, but on the West and the invaded Ukraine. In the narrative Fidesz has constructed, the West should have never intervened in the Russian-Ukrainian war (since it was not a NATO member that was attacked), and if it had not intervened, Kyiv would have bled to death in no time, so there would be no war – so the argument goes.

However, the way Orbán has been talking about Ukraine most recently is a whole new level even when compared with his previous statements, and this is probably not unrelated to the fact that Trump's approach to Kyiv is quite different from that of the previous US administration. Beyond talking about the EU as an empire in the worst sense of the word, Orbán now claims that this ‘empire’ wants to colonise Ukraine. But in a somewhat contradictory way, he also claims that the EU wants to fund the Ukrainians, or, as he put it in a subsequently deleted message on a social media platform: that it wants to keep Ukraine alive.

No way back

There is no doubt that Orbán will not be making another U-turn in the near future, as his political identity has become solidified and it currently seems that other than speaking to the core voters of Fidesz, he has also begun courting the sympathisers of Mi Hazánk and even the far-right party itself. In addition, according to some interpretations, the reason for his boldness in banning Pride is that he wants to set a trap for the Tisza Party, which is a threat to Fidesz. According to this view, if Péter Magyar picks up the gloves on these ideological issues, he will be grouped with the "old opposition" and play the role Fidesz has pre-assigned to him, but if he does not make his voice heard on this issue, he could lose voters among those who care about the rule of law.

But whatever the explanation for the latest step in Putinisation, it is still clear that if this is to be Fidesz's path, the Prime Minister will continue to reinforce the Hungarianisation of the Russian model, with ideological issues becoming even more prominent.

The overwhelming majority of pro-government and Mi Hazánk voters are already pro-Russian, or at least are against Ukraine. According to a February poll by IDEA Intézet, the voters of both parties believe that Ukrainians are more to blame for the delay in ending the Russian-Ukrainian war, but at the very least, they believe that the warring parties share equal responsibility.

Of course, the Hungarian hybrid regime cannot be compared with Russia or even Belarus, whose leaders no longer bother tampering with the law, but are staying in power by force and if necessary, are jailing the opposition and are not shying away from electoral fraud or from cooperating with organised criminal groups.

In addition to the well-known handouts and promises, the Hungarian Government is trying to achieve its political goals by means of communications campaigns, by drafting and amending laws, by repeatedly rewriting the Fundamental Law, by symbolic politicking and by badgering the opposition, as well as trying to embarrass its main political opponent, but a violent solution remains out of the question, even for them. A good example of this is that they even want to avoid the organisers or participants of Pride – if the event is held – having the option of serving time instead of paying the fine imposed. However, amending the law on assembly in order to ban Pride represents the crossing of a line that moves the country one step closer to Putin's Russia.

For the time being, the Hungarian model only contains the ideological software, the hardware is missing, and since Fidesz is not relying on violence, in this respect it is far removed from the Russian system. For now, the Hungarian regime is trying to win the political race on the playing field that was designed to suit it best, and is trying to make up for the shortcomings in its governance, inflation, the housing crisis, in short, a whole series of problems that voters experience in their everyday lives, through ideology and the distribution of money. At the moment, there is also no sign that the Sovereignty Protection Office will become anything more than a state organisation designed to stigmatise independent media, journalists, and NGOs critical of the government.

So far, only Momentum (which is fighting for getting into parliament in 2026) and Gergely Karácsony, the mayor of Budapest, have stepped into the ideological-communication battle. For tactical reasons, even the Tisza Party, considered the strongest opposition force, has not taken up the cause of the rule of law, i.e. the banning of Pride. Orbán is probably calculating that banning Pride poses no political risk to Fidesz, but it could dig a bigger trench in an already polarised society, divide Tisza supporters and strengthen some of the forces of the "old opposition".

Even if the banning of Pride was driven by crude political calculations, all that has been going on since 2010 proves that what they have been doing at home and abroad is much more than a simple power game, as the regime was already drawing on Russian elements when it had no significant political opponent at home. And there are certain moves (such as Orbán's meddling in Bosnia) which cannot be explained at all in this domestic political sphere, and which have no communicative value whatsoever.

But even if we accept that this, i.e. dominating the moment, regaining or retaining control over the political agenda, or provoking the opposition, is the sole purpose of banning Pride, the fact remains that by following the Russian model, Fidesz went after a fundamental right gained at the time of the regime change. And in doing so, it has taken another step on the road that one way or another will eventually lead to Moscow.

For more quick, accurate and impartial news from and about Hungary, subscribe to the Telex English newsletter!